Remembrance

SUFFERING OF MILUTIN JANJUŠEVIĆ (1896–1941), MANAGER OF THE NATIONAL THEATER IN SARAJEVO, IN THE EVE OF WORLD WAR II

In a Pit and Oblivion

As a young man from Herzegovina, he escaped to the Serbian army in 1914 and survived the tortures through Albania. From Greece he was taken to Cambridge and returned to his homeland after completing his educating. He revived the National Theater in Sarajevo and became a reputable local Serb. This cost his life in 1941, immediately after the establishment of the Croatian occupational government. He was killed in Jadovno in July 25. There is no memorial or monument in Sarajevo or Srpska. Let us rectify it

By: Sandra Kljajić

Photo: Private Archive

Although he moved to Sarajevo and probably set foot in it for the first time only after completing his education, in the early 1920s, his name is mostly related to that city. He was most famous as manager of the National Theater in Sarajevo from 1930 to 1941, while publicly available information about him, pretty vague, states that before the Theater he was professor of history and geography in the Second Male Gymnasium in the city.

Although he moved to Sarajevo and probably set foot in it for the first time only after completing his education, in the early 1920s, his name is mostly related to that city. He was most famous as manager of the National Theater in Sarajevo from 1930 to 1941, while publicly available information about him, pretty vague, states that before the Theater he was professor of history and geography in the Second Male Gymnasium in the city.

However, as his granddaughter Irina Đorđević says, Milutin Janjušević was much more than that.

– Before all, he was dedicated to the society with his entire heart – says daughter of Milutin’s son Zoran.

There are numerous photos and documents, a dozen cards from the concentration camp, Albanian Memorial and a diary, testifying about Milutin’s life. Irina keeps them with special love and care.

Milutin was killed twenty years before her birth and everything Irina knows about segments of his life is from stories of family members, mostly from what her grandmother Nevenka Janjušević, Milutin’s wife, wrote in her diary.

– Grandma started keeping a diary in 1961, when I, her first grandchild, was born. She wrote down historical events and those related to our family, as well as her memories of grandfather. Several notebooks are preserved, and one of them keeps writings about Milutin.

According to his birth certificate, Milutin was born on September 27, 1896, in Velika Gareva, Gacko Municipality, homeland of many famous Serbs. Several decades later, some of them became an unbreakable part of his life. Born in a rural family, he lived a peasant life as a boy, but he was an excellent student. Thus, after completing elementary school, his parents sent him to the gymnasium in Mostar, a convent at the time.

According to his birth certificate, Milutin was born on September 27, 1896, in Velika Gareva, Gacko Municipality, homeland of many famous Serbs. Several decades later, some of them became an unbreakable part of his life. Born in a rural family, he lived a peasant life as a boy, but he was an excellent student. Thus, after completing elementary school, his parents sent him to the gymnasium in Mostar, a convent at the time.

Milutin’s mother died young, and before he completed the gymnasium, World War I broke out.

– For Milutin and his father Đoka, Serbian patriots, it was out of the question to go to war on the Austro-Hungarian army side. To avoid mobilization, they escaped together with grandpa’s younger brother Pero to Montenegro, intending to join Serbian volunteers. It was a very difficult journey, but they succeeded. I know that all three of them were in the same unit, and that they were in Serbia in 1914.  The following year, when the army started retreating, my great-grandfather, grandfather Milutin and Pero managed to cross Albania. However, my great-grandfather stayed in the Blue Tomb – tells Irina.

The following year, when the army started retreating, my great-grandfather, grandfather Milutin and Pero managed to cross Albania. However, my great-grandfather stayed in the Blue Tomb – tells Irina.

In Greece, French and English ships boarded young soldiers and took them to France and England for education.

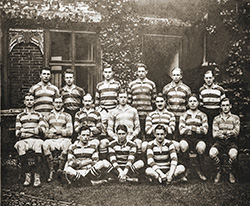

– Thus, Milutin and Pero ended up in England, in Cambridge. My grandfather continued his education in the gymnasium, and later at college. The conditions for education were excellent. They lived in a campus, went to school, played sports, participated in cultural associations… My grandfather often watched theatrical plays, and perhaps that was where his love for the theater began. Even besides all that, they were nostalgic. My grandmother wrote that Serbian students performed plays for the English and cried while singing the song ”There, Far Away” at the end of the play – says Irina.

SARAJEVO

After completing his education, Milutin returned to his homeland – Kingdom of Serbs, Croatians and Slovenians, or to be more exact, to Bosnia and Herzegovina. Pero also completed his education in Cambridge and went to Belgrade. Nevenka wrote in her diary that Milutin was offered to stay in England but believed that his country needed him more.

After completing his education, Milutin returned to his homeland – Kingdom of Serbs, Croatians and Slovenians, or to be more exact, to Bosnia and Herzegovina. Pero also completed his education in Cambridge and went to Belgrade. Nevenka wrote in her diary that Milutin was offered to stay in England but believed that his country needed him more.

– He wanted to participate in rebuilding the country – emphasizes Irina.

He first went to his birthplace, Gareva, which he was very proud of and loved until the end of his life.

– Gareva was completely destroyed. My grandfather had the knowledge, strength and experience, so he brought together the peasants from Gareva. They first renovated the school and then everything else – tells Irina.

He then went to Sarajevo, where he was appointed professor of history and geography in the Second Male Gymnasium.

– He liked working with young people, and they could learn a lot from him. He didn’t simply stick to the program. He took students to field trips all over Yugoslavia and abroad. Besides what they were learning in school, he believed that they should learn to do something else as well. All his students had to know three things: to bind books, ride a bike, and take photos. He was member of the Sokol Association, member of the Railway Students’ Home in Ilidža board… He was strict and requested discipline, but according to my grandma’s stories, students loved him – says Irina.

– He liked working with young people, and they could learn a lot from him. He didn’t simply stick to the program. He took students to field trips all over Yugoslavia and abroad. Besides what they were learning in school, he believed that they should learn to do something else as well. All his students had to know three things: to bind books, ride a bike, and take photos. He was member of the Sokol Association, member of the Railway Students’ Home in Ilidža board… He was strict and requested discipline, but according to my grandma’s stories, students loved him – says Irina.

It wasn’t difficult for versatile, hard-working, intelligent and educated Milutin, who spoke two foreign languages (German and English) and was successful in everything he tried, to find his way in Sarajevo. Although without any connections, he soon became part of the then city elite.

He participated in the work of the National Theater. In late 1930, he became manager of this cultural institution, succeeding famous writers Branislav Nušić and Mirko Korolija. He kept the function longer than any of his predecessors – eleven years. The National Theater states that he stabilized working conditions, enlarged the ensemble, modernized the repertoire and opened possibilities for stage experiment. He also tried to modernize  the scene, expanded the scenography and costume fundus, and brought Vasa Kosić, director. He announced a competition for best local drama, which grew into a Fund for awarding local drama texts, actors, directors and scenographers.

the scene, expanded the scenography and costume fundus, and brought Vasa Kosić, director. He announced a competition for best local drama, which grew into a Fund for awarding local drama texts, actors, directors and scenographers.

The degree of his success is shown in the text ”Fifteen Years of the Sarajevo Theater” published in the Serbian Educational and Cultural PKD ”Prosvjeta” Calendar on January 1, 1936, a bit more than five years since his appointment as manager. It states that ”today this theater is the common good of a spacious environment which significantly crosses the boundaries of the Drina Banate. Its cultural influence is growing from season to season, its audience is, therefore, becoming more numerous, and thanks to that fact, its artistic level is showing a continuous incline. The repertoire policy of the Theater managed to bring Yugoslav drama, which is now intensively cherished and developed, on the same level as foreign drama, coming from great nations with long theatrical traditions and high theatrical culture. Today, the number of Yugoslav writers played on the Sarajevo stage is equal to the number of foreign ones…”

FAMILY

The 1930s were the happiest years in Milutin’s life. He married Nevenka Grđić in 1930 in Sarajevo. Nevenka (birth name Nevena) was born in 1901 in Sarajevo, where she grew up. She came from a famous family from Gacko – her father was Šćepan and her uncle was Vasilj Grđić, reputable educational workers and fighters against Austro-Hungarian oppression.

The 1930s were the happiest years in Milutin’s life. He married Nevenka Grđić in 1930 in Sarajevo. Nevenka (birth name Nevena) was born in 1901 in Sarajevo, where she grew up. She came from a famous family from Gacko – her father was Šćepan and her uncle was Vasilj Grđić, reputable educational workers and fighters against Austro-Hungarian oppression.

– Nevenka and Milutin knew each other by sight while she was in the final grade of the Female Gymnasium and he was professor in the Second Male Gymnasium, because both schools were in the same building. Her father insisted that, besides his son, his daughters should also graduate from the university, so after completing high school, my grandmother went to study in Zagreb. Love between them was born several years later, when she returned to Sarajevo after graduation and started working as history and geography professor at the Female Gymnasium – tells Irina.

She was similar to him – with a modern mentality, educated and socially engaged. She worked as school secretary and, besides history and geography, occasionally taught Serbian and German language.

She was similar to him – with a modern mentality, educated and socially engaged. She worked as school secretary and, besides history and geography, occasionally taught Serbian and German language.

– They were in a relationship for a long time. Although she loved my grandfather very much, she couldn’t decide to marry him, because she was particularly attached to her family. In the year 1931 their daughter Smiljka was born, and three years later their son Zoran, my father – tells Irina.

They lived a happy family life in an apartment in Sarajevo. Milutin also built a summer house in Pale, where they stayed during the summers and spent their free time. They were friends with famous historian and Germanist Pero Slijepčević, also Herzegovinian (from Samobor, Gacko Municipality) and his wife Ljuba. They also had a summer house in Pale.

– Grandma spoke about grandfather with great love until the end of her life. She said that she wouldn’t change the eleven years she had spent married to him for anything in the world, that he was a wonderful father and husband. He was very gentle towards his children but insisted on discipline. He worked very hard. Upon returning from work in the evening, the children would ask him whether he was going to the theater. If he said he wasn’t, they would start a real celebration – says Irina.

– Grandma spoke about grandfather with great love until the end of her life. She said that she wouldn’t change the eleven years she had spent married to him for anything in the world, that he was a wonderful father and husband. He was very gentle towards his children but insisted on discipline. He worked very hard. Upon returning from work in the evening, the children would ask him whether he was going to the theater. If he said he wasn’t, they would start a real celebration – says Irina.

Nevenka wrote down in her diary: ”He loved children with joy, I loved them with care. I always worried how and what and he used to tell me to enjoy the children. Once he said: ’Who knows, perhaps one day you will be both their mother and father.’”

ARREST AND DEATH

As if he had anticipated his tragic fate. In 1941, after the Ustashas rose to power, their first target were the most reputable Serbs, including Milutin Janjušević. He was arrested already on May 2, 1941.

As if he had anticipated his tragic fate. In 1941, after the Ustashas rose to power, their first target were the most reputable Serbs, including Milutin Janjušević. He was arrested already on May 2, 1941.

– He was imprisoned in Sarajevo. Grandma tried to get him out of prison, but it was impossible. He was then transferred to Koprivnica, to ”Danica”, the first Ustasha concentration camp in then Independent State of Croatia, and later to Jadovno – continues Irina.

Milutin sent cards from Koprivnica, so the family was in contact with him for a short time.

– It was all, of course, censored, so he couldn’t write anything about his stay there or how difficult it was for him. He wrote to his family how much he loved and missed them. He instructed Nevenka what to do with the household and money… He wrote in small letters so that he could say more. On one of his last cards, he sent a message to his children: ”Daddy’s pride, mommy is writing that you are well and listening to her. It makes me happy.” He wrote them to be good, healthy and joyful and that daddy loves them very much – tells Irina.

Nevenka received the last card from him on June 29, 1941.

Nevenka received the last card from him on June 29, 1941.

She found out that Milutin was killed, but only later discovered when exactly, so she wrote in her diary: ”They say it was in Jadovno concentration camp on Velebit, on July 25, 1941.”

– Milutin was persecuted even after his death. Grandma was proclaimed his representative. They requested him to apply for a job, although he was no longer alive. Neither grandma nor her sisters wanted to work for the Ustasha authorities. My grandma, dad and aunt were afterwards banished from the apartment – says Irina.

Nevenka returned to her parents together with Zoran and Smilja. Her sister and brother helped her raise and educate the children.

– For my grandma, father and aunt, Milutin’s death remained a sore point forever. They missed him very much. They often spoke about him, especially my aunt, who remembered him more than my father did – says Irina.

– For my grandma, father and aunt, Milutin’s death remained a sore point forever. They missed him very much. They often spoke about him, especially my aunt, who remembered him more than my father did – says Irina.

Today, only members of the Janjušević family and a few theater lovers know about Milutin Janjušević.

– He left Gacko early, while Sarajevo, unfortunately, completely forgot him. There is no tomb, no monument, or anything dedicated to him. He raised the National Theater to its feet and contributed to the cultural development of Sarajevo. His destiny is a testimony of the suffering of Serbs in World War II. Thus, I hope that he will get a place he deserves, even after so much time. At least an exhibition. Reminiscence of his life indicates how to love homeland and people, how to raise young people and how to protect the family – concludes Irina.

***

Nevenka’s Death

Nevenka Janjušević stayed in Sarajevo until the end of her life. She died at the age of 92, in May 1992.

– A year or two before death, she and her younger sister Bosiljka went to live in a geriatric institution in the Sarajevo neighborhood Nedžarići. Grandma was still healthy and vital, but due to bad conditions, she caught a cold and then pneumonia. Aunt Smiljka informed us through radio amateurs that grandma died and that she was buried on the cemetery in Bare, Sarajevo – says Irina.

Zoran passed away in 1994 and Smiljka in 2014.

***

Visit to Kosovo

Milutin published texts in the SPKD ”Prosvjeta” Calendar in the 1930s. He wrote about Kosovo, about his visit to Zvečan, with particular love.

***

Magazine and New Building

At the time Milutin Janjušević was manager of the Theater, the magazine ”Sarajevo Stage” was established. Its editor was drama writer Borivoje Jevtić. He tried to have a new, modern theater building raised in Sarajevo, so on December 1, 1940, for the 20th anniversary of the National Theater, a foundation stone was laid. The building was never constructed.